Several months ago, I wrote a column in Multiple Sclerosis News Today about Andrew Barclay.

Barclay died in an assisted suicide in December. He’d had multiple sclerosis for many years.

Colin Campbell is a 56-year-old MS patient who lives in Inverness, Scotland. He also wanted to die. In fact, he was scheduled to end his own life, with help, on June 15 at a suicide clinic in Switzerland. But he changed his mind.

Campbell has been writing about his MS for the Sunday Herald in Glasgow since late April. (He’s also the paper’s “Beer of the Week” writer.) He describes himself as “a man on death row,” and on May 20, his MS article began, “Well, unfortunately I am still alive.”

Campbell has mobility problems, and living in a second-floor flat has been tough for him. He says he’s had no support in getting ground-floor accommodations. He complains that he was recently discharged from a hospital without the possibility of receiving home care. He has no caregivers and exists on microwave dinners.

Campbell had hoped that a stem cell transplant would allow him to live a life that was worth living, but his neurologist told him that he thought HSCT would be too risky. So, at age 56, Campbell made plans to die.

Then came a glimmer of hope. In a column he wrote two days after he had been planning to die, Campbell explained that a former police sergeant named Rona Tynan gave him a reason to live, at least a little while longer.

“Rona, who also has multiple sclerosis, was of the opinion that I should not commit suicide until having tried every other possible avenue – including soon-to-be-available multiple sclerosis treatments for folk like me with primary progressive MS. Rona persuaded me, and I agreed,” Campbell wrote.

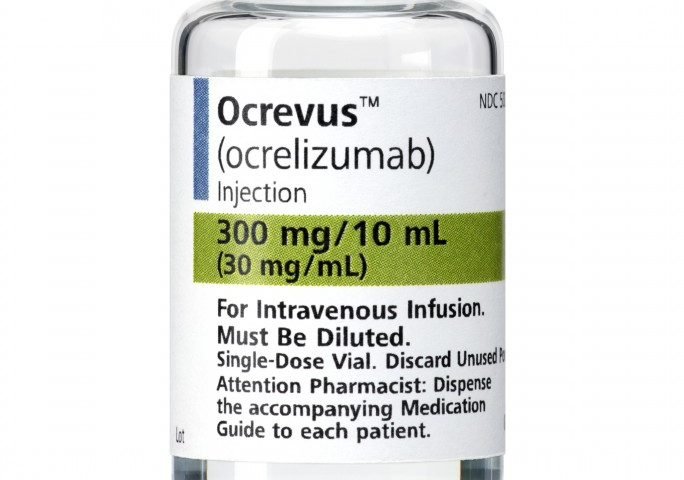

That treatment is the disease-modifying drug ocrelizumab, sold in the U.S. under the brand name Ocrevus. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved it a few months ago, and it’s the only drug approved to treat progressive MS. Some neurologists refer to it as “stem-cell lite” because of the way it attacks the rogue B-cells that are believed to cause MS. Ocrelizumab is expected to be available in Scotland later this year.

“For the first time since multiple sclerosis was identified during a post-mortem 149 years ago, there now seems to be a real hope of lasting risk-free treatment for multiple sclerosis sufferers within the next few years,” Campbell writes. “The timing could not have been more perfect — although there was a fear, of course, that the developments had just come too late for me. But I wanted to remain as optimistic as possible.”

Colin Campbell’s hope, now, is that Ocrevus will halt the progression of his MS and avoid a future that he pictures as becoming bedridden, needing help to eat and bathe, and using a catheter. He’s not sure how much hope he realistically should have, but he ends his June 17 column with: “Wish me well.”

That, we certainly do.

****

(This post first appeared as my regular column on www.multiplesclerosisnewstoday.com)